|

|

|

|

Historical Sketch

The material in this online collection illustrates George Washington's involvement, mainly in western Pennsylvania, at various points in his long career. This chronology is not intended to be comprehensive, but serves to place the items in this collection into historical context.

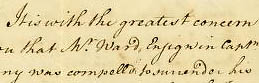

The online exhibit of manuscripts begins with the newly promoted twenty-two year old Lieutenant Colonel Washington leading Virginia troops into the Ohio River Valley seeking to displace the French and reconstruct a permanent fortification at the "forks of the Monongahela" river (present day Pittsburgh). Washington is credited with discovering this strategic point in 1753 while scouting the area at the behest of Robert Dinwiddie, Royal Governor of Virginia. A small fort was erected and then lost to the French. While seeking to protect land interests in 1754, Washington's troops initiated the first shots of the French and Indian War on the 28th of May and constructed Fort Necessity. Two letters in the collection document this time period, one to James Hamilton, Governor of Pennsylvania, indicating the loss of the fort (1); and the second to Robert Dinwiddie on May 29, 1754 reporting on spies (2). Later that summer Washington surrendered Fort Necessity and returned with his troops to Virginia. The online exhibit of manuscripts begins with the newly promoted twenty-two year old Lieutenant Colonel Washington leading Virginia troops into the Ohio River Valley seeking to displace the French and reconstruct a permanent fortification at the "forks of the Monongahela" river (present day Pittsburgh). Washington is credited with discovering this strategic point in 1753 while scouting the area at the behest of Robert Dinwiddie, Royal Governor of Virginia. A small fort was erected and then lost to the French. While seeking to protect land interests in 1754, Washington's troops initiated the first shots of the French and Indian War on the 28th of May and constructed Fort Necessity. Two letters in the collection document this time period, one to James Hamilton, Governor of Pennsylvania, indicating the loss of the fort (1); and the second to Robert Dinwiddie on May 29, 1754 reporting on spies (2). Later that summer Washington surrendered Fort Necessity and returned with his troops to Virginia.

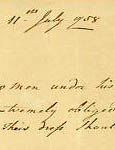

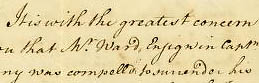

After the 1755 disastrous Braddock campaign to gain Fort Duquesne, Washington was appointed Colonel and commander of the Virginia forces. While Colonel, Washington was responsible for keeping the outposts free of Indian attacks, but was not given the authority to devise strategy, which rested solely with the British Army. Lack of support from the colonial Virginia government precipitated supply shortages, noted in this collection by a letter to Washington from General George Bouquet, July 11, 1758 (3). Bouquet also refers to British officer General John Forbes, who Washington joins several months later to take Fort Duquesne. Troops reached the fort and found that it had been burned and abandoned before their arrival, marking a bittersweet victory. The fortification was again built on the same site and named after the British statesman, William Pitt. After the 1755 disastrous Braddock campaign to gain Fort Duquesne, Washington was appointed Colonel and commander of the Virginia forces. While Colonel, Washington was responsible for keeping the outposts free of Indian attacks, but was not given the authority to devise strategy, which rested solely with the British Army. Lack of support from the colonial Virginia government precipitated supply shortages, noted in this collection by a letter to Washington from General George Bouquet, July 11, 1758 (3). Bouquet also refers to British officer General John Forbes, who Washington joins several months later to take Fort Duquesne. Troops reached the fort and found that it had been burned and abandoned before their arrival, marking a bittersweet victory. The fortification was again built on the same site and named after the British statesman, William Pitt.

Washington subsequently returned to his home at Mount Vernon in Virginia, where he ran the family plantation and acquired land.  The collection includes an original survey of land granted to Washington for his services to the colony of Virginia in the French and Indian war along with his autographed acceptance dated November 6, 1772 (4, 5). A letter from Washington in 1774, previous to the first Continental Congress, requests that a friend, who had received land resulting from the 1763 Treaty of Paris, select a surveyor who was a personal friend and highly recommended (6). Washington stepped back into public life as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress. As the second congress concluded, he was called upon to lead the new Continental Army. The collection includes an original survey of land granted to Washington for his services to the colony of Virginia in the French and Indian war along with his autographed acceptance dated November 6, 1772 (4, 5). A letter from Washington in 1774, previous to the first Continental Congress, requests that a friend, who had received land resulting from the 1763 Treaty of Paris, select a surveyor who was a personal friend and highly recommended (6). Washington stepped back into public life as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress. As the second congress concluded, he was called upon to lead the new Continental Army.

As Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, Washington wrote to General Hand, located at Fort Pitt, just after forces were defeated at Germantown, 1777. Washington instructs Hand to send the 8th Pennsylvania Regiment to his camp, but also recognized the state of the garrison at Fort Pitt and the attitude of the neighboring inhabitants in furnishing assistance (7). This communication was issued in October before Washington takes the troops to Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, for the winter. The letter to Hand suggests the lack of supplies and coordination across the colonies.

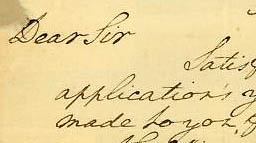

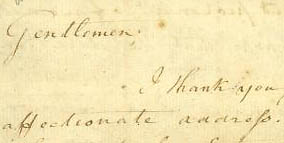

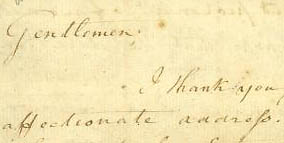

Following the Revolutionary War, Washington returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon. In 1789, he became the first President of the United States. In 1794, during Washington's second presidential term, farmers in western Pennsylvania refused to pay taxes on the manufacturing of whiskey and violently attacked federal officials. Washington swiftly crushed this rebellion and set about restoring order. A letter written by Washington, during the Whiskey Rebellion, reassures the town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and thanks them for their "affectionate address" (8).

Following the Revolutionary War, Washington returned to his plantation at Mount Vernon. In 1789, he became the first President of the United States. In 1794, during Washington's second presidential term, farmers in western Pennsylvania refused to pay taxes on the manufacturing of whiskey and violently attacked federal officials. Washington swiftly crushed this rebellion and set about restoring order. A letter written by Washington, during the Whiskey Rebellion, reassures the town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and thanks them for their "affectionate address" (8).

George Washington concluded his second presidential term in 1796 and retired to Mount Vernon.

The last two items in the collection concern Washington's land transactions, the first disposing of land in western Pennsylvania in 1795 (9), and the second a letter to his nephew, Robert Lewis, in 1798 discussing crops and land leases (10). Washington died on December 14, 1799.

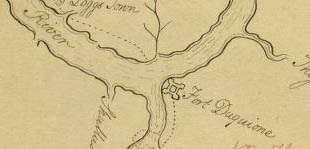

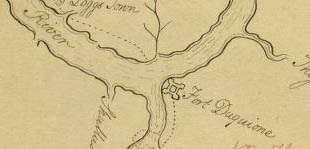

In addition to the manuscript material drawn together in this online collection, we have included several other items that document Washington's life. The first is a watercolored print, rendered by William Stott and published in Philadelphia, that portrays the young Lieutenant Colonel Washington at twenty years of age on his way to Pittsburgh in 1754 (11).  The second is a hand-drawn map that depicts the region of the Cumberland Gap and western Pennsylvania up to Lake Erie (12). Created two years after Washington reached the Forks of the Monongahela in 1754, the map traces the rivers and settlements along this common trade route, including Fort Cumberland, Great Meadows, Fort Duquesne, Mingo Town, and Murdering Town. The map was hand copied by James A. Burt in 1882 from the original 1756 map located in London at the British Museum. William M. Darlington, an avid collector of western Pennsylvania history, commissioned Burt to copy the map created by the British Army serving under General Braddock. The map references the paved and repaved area created by British troops in 1755 along the Monongahela River where General Braddock was buried. Washington provided the eulogy at Braddock's memorial service before his unmarked grave became part of the trail. The second is a hand-drawn map that depicts the region of the Cumberland Gap and western Pennsylvania up to Lake Erie (12). Created two years after Washington reached the Forks of the Monongahela in 1754, the map traces the rivers and settlements along this common trade route, including Fort Cumberland, Great Meadows, Fort Duquesne, Mingo Town, and Murdering Town. The map was hand copied by James A. Burt in 1882 from the original 1756 map located in London at the British Museum. William M. Darlington, an avid collector of western Pennsylvania history, commissioned Burt to copy the map created by the British Army serving under General Braddock. The map references the paved and repaved area created by British troops in 1755 along the Monongahela River where General Braddock was buried. Washington provided the eulogy at Braddock's memorial service before his unmarked grave became part of the trail.

The last two items are broadsides created in the final decade of Washington's life. The first, a presidential proclamation of 1795, promotes a day of national Thanksgiving to be recognized and celebrated on February 19th of that year (13). Washington encouraged this holiday throughout much of his presidency despite opposition from some states that the hardships of the Pilgrims did not reflect their own cultures and lifestyles, and thus did not warrant a national holiday. The final item, a broadside of December 29, 1799, details a funeral march for George Washington (14). The document enumerates the activities involved in the somber New York City procession. --Kate Colligan, Archivist, Archives Service Center |

|