Clinton Impeachment Trial

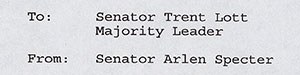

“Not proven and therefore not guilty.” (Senator Specter’s February 12, 1999 vote on the two charges against President Clinton)

One of the defining political moments of the 1990s in America was the impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton. Playing out over the latter half of the decade, the trial became a national sensation involving talking points on sexual impropriety, perjury, and partisanship. By the time to final Senate vote would held in February 1999, the case had taken on a life of its own. Arlen Specter’s sole vote of “not proven and therefore not guilty” was one of many peculiar episodes in a very unusual trial.

The charges against Clinton had their basis in a sexual harassment lawsuit brought by Arkansas state employee Paula Jones against him in 1994. In trying to establish that Clinton’s behavior had a precedent, Jones’ lawyers were made aware of Monica Lewinsky, a former White House intern. Lewinsky had been unknowingly recorded describing a sexual relationship with Clinton to a friend. Kenneth Starr, an Independent Counsel, launched an investigation into the matter, detailing in what would be referred to simply as “the Starr Report,” that Clinton had directed Lewinsky to file a false affidavit and deny any nonprofessional relationship between the two.

In a sworn deposition given in 1998, Clinton testified under oath that there was no sexual relationship between himself and Lewinsky. Starr’s investigation alleged that the president had knowingly lied under oath when giving this statement. Though criticized for containing unnecessary embarrassing details and for unethically being leaked to the press, the Starr Report was the basis of the House of Representatives’ vote to impeach Clinton on two charges in December 1998: perjury, and obstruction of justice.

The trial began in the Senate on January 7th, 1999, with Chief Justice William Rehnquist presiding. As the details of the procedures for the trial were being decided, Senator Specter expressed dissatisfaction with the Senate’s decision not to call live witnesses in the trial. Instead, the Senate called for the depositions of three people, including Lewinsky, which would then be shown via video recording to the full Senate. Other evidence was given by 13 House Managers from the House of Representatives over three days, followed by a rebuttal from Clinton’s defense counsel. As the House had not conducted a separate investigation, instead relying on the Starr Report, which Specter found to be incomplete.

Two days before the final vote, Specter announced his decision to vote “not proven,” citing Scots law as a precedent. In Passion for Truth, he summarized his reasoning:

Citing the Senators’ oath to do “impartial justice,” I concluded that the Senate had only done “partial” justice, because we had cut the process short and not given the House managers a chance to prove their case. The Senate declined to hear live witnesses, which is the essence of a trial. The Constitution is explicit that the Senate has an obligation to try the case. I intended to vote “not proven,” because there had been no trial and therefore no foundation for a finding of “guilty” or “not guilty.” (517)

No stranger to controversial decisions, Specter received criticism on both sides of the aisle for his vote, including accusations that he was only trying to be contradictory, or that he was disregarding the House’s findings. Others backed up his position, taking the stance that the trial had been a “sham” and had never actually convened with the intent to fully investigate the charges. In the end, Specter’s actions revealed him once again to be a man who stood by his own convictions and understanding of the law even in moments of intense political pressure.