Tsukioka Kōgyo 月岡耕漁 (1869-1927) is the preeminent graphic artist of the nō and kyōgen theatres. Over a third of a century from the early-1890s until his premature death in 1927, Kōgyo created hundreds of paintings, prints, magazine illustrations, and postcard pictures of nō and kyōgen plays. Kōgyo also produced paintings and prints of flowers, birds, and genre and even wartime scenes, but it is for his theatre paintings and prints that he is best known and remembered.

Kōgyo was born on March 7, 1869, as Hanyū (sometimes read as Habu) Bennosuke (sometimes rendered in English-language sources as Sadanosuke) 羽生弁之助 (also 辨 or 辯) the second son of a family that ran an inn named the Ōmiya in Nihonbashi, a renowned “downtown” district of Tokyo. In 1880, his mother Taiko returned with Bennosuke to her natal home (in nearby Hongoku-cho, just behind the present-day Bank of Japan building), and he was adopted into her family, the Sakamaki 坂巻, the name under which his paintings and prints before 1911 were issued. Bennosuke then apprenticed in pottery painting with his uncle, an exporter of Japanese ceramics, in Yokohama. In 1883, he studied briefly at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, before moving at age fifteen to Fukushima Prefecture in the far north to teach painting on pottery. In 1887, while still a teenager, Bennosuke entered the atelier of one of the most prominent Meiji period woodblock print artists, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, where Kōgyo learned the fundamentals of painting. Yoshitoshi, who had married Taiko in 1884, gave him the name Toshihisa (The toshi 年 was taken from his stepfather’s name—the Japanese equivalent of “junior.”) In 1889, Bennosuke/Toshihisa went to study with Ogata Gekkō 尾形月耕, another important late nineteenth-century Japanese painter and printmaker, with whom the young artist studied painting flowers and birds, at which he excelled, shading, and painting on silk. It was Gekkō who gave the young artist the name Kōgyo, made up of two Chinese characters, characteristically, since Toshihisa was a prized disciple, one from his own name meaning “to cultivate crops” and the other meaning “to fish.” Kōgyo also studied with the Japanese-style painter, Matsumoto Fūko 楓湖, from whom he received yet another name, Kohan 湖畔, which again included a character from Fūko’s own name. After Yoshitoshi’s death in 1892, Taiko succeeded as head of his school, even though she herself was not an artist. In 1911, according to her will, Kōgyo adopted Yoshitoshi’s surname and assumed the headship of the school. Thus in his early forties, Sakamaki Kōgyo finally had the name with which he is best known to the art and nō world: Tsukioka Kōgyo. 1

Yoshitoshi inculcated in Kōgyo a lifelong interest in the nō theatre. In the 1880s, Yoshitoshi, who had worked with Kuniyoshi, also a portrayer of nō subjects, took up the study of utai (nō chanting) and shimai (dancing) with Umewaka Minoru, one of the three great nō actors of the Meiji era. Nō performance, which had been intimately connected with the feudal ruling class before the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868, lost favor as Japan set out to modernize on the Western model in the 1870s. Moreover, nō had to compete for audiences not only with other kinds of traditional theatre such as kabuki and the puppet theatre, also trying to save themselves, but also with a variety of new forms imported or adapted from the West. Umewaka, together with the actors Sakurama Banma and Hōshō Kurō, and the aristocratic government leader, Iwakura Tomomi, played a major role in reviving nō by tying its performance tradition to the imperial family and the newly recreated imperial mystique. Iwakura, who had been taken by leading Western government officials to opera performances in Europe during his famous mission there in 1871-3, decided that nō could play a similar role for foreign visitors to Japan—it was both indigenous and elegant. Iwakura persuaded the emperor and other dignitaries, most of whom were ex-samurai with a long tradition of patronizing “ritual nō” (shikinō式能) in the late feudal period, to follow his advice, and in the summer of 1879 the emperor entertained the visiting American ex-president, Ulysses S. Grant, at a nō performance. After seeing Hōshō and two other actors perform Mochizuki, Tsuchigumo, and a kyōgen play, Grant said to Iwakura, “It is easy for a noble and elegant art like this one, being influenced by the times, to lose its dignity and fall into decline. You should treasure and preserve it.” 2

Graphic representations of nō themes were important to this revival of nō—in fact, the print artist Toyohara Chikanobu created a triptych entitled Illustration of a Nō Performance at the Temporary Imperial Palace at Aoyama, which shows Umewaka performing Shōzon, a play about an attempt to assassinate the famous Genji general, Yoshitsune, before the emperor at the imperial palace. Yoshitoshi, and to a much greater degree his stepson Kōgyo, and then Kōgyo’s daughter Gyokusei 玉瀞 and disciple Matsuno Sōfū 松野奏風, were key players in the modern popularization of nō. Kōgyo produced over six dozen nō paintings, created five sets of prints (around 700 individual prints) and many individual prints of nō and kyōgen subjects, over one hundred illustrations of nō and kyōgen plays (and half as many non-nō illustrations) for Japan’s first graphic magazine, Fūzoku gahō, and produced small postcard prints to be sold by the nō publishing house, Wan’ya. Two early twentieth-century English-language works on Japanese theatre used Kōgyo’s prints as illustrations. Osman Edwards published Japanese Plays and Playfellows in 1901, and of the twelve color illustrations in the book, five are by “Mr. Kogyo.” Marie C. Stopes, famous as a British botanist, suffragette, and birth control advocate, used seven Kōgyo prints in her 1913 book of translations, Plays of Old Japan: The Nō.

In 1911, when he succeeded to the headship of Yoshitoshi’s school, Kōgyo was associated with the Art Association (Bijutsu kyôkai) and the Jitsugetsukai 日月会, at whose exhibitions he often exhibited and won prizes for his paintings—and later in his career, he served as a judge as well. His paintings and prints include those of flowers, birds, people, as well as scenes from nō plays. He also did prints of battle scenes during the Sino-Japanese War in 1894-5—some of which appeared in Fūzoku gahō. His painting, “The Horse Market at Kiso,” for example, won a prize at the San Francisco World Fair.

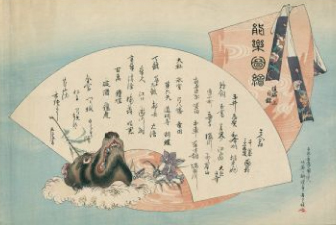

Kōgyo began painting images of nō in his late twenties and gained attention with his paintings of the plays Dōjōji (1899) and Hagoromo (1901, and five more times between 1902 and 1919), and of The Empress Viewing Nō. The Meiji Empress bought the latter for the Imperial Household. Between the 1890s and his death on February 25, 1927, Kōgyo produced five major sets of nō prints: “Illustrations of Nō,” (Nōgaku zue) 能楽図絵 (261 prints, including 221 prints of 220 nō plays, 27 prints of kyōgen plays, and 13 miscellaneous prints: tables of content, illustrations of masks, etc.); “One Hundred Prints of the Nō,” (Nōgaku hyakuban) 能楽百番 (100 plays, 122 sheets since some are diptychs and triptychs); An Album of Nō Prints (Nōgaku gafū) 能楽画譜, 12 prints of nō plays; “Fifty Prints of the Kyōgen Theatre (Kyōgen gojūban) 狂言五十番, 16 done by Kōgyo and 34 plus a table of contents by Gyokusei (under the name Kôbun江文; and “A Great Collection of Nō Pictures,” (Nōga taikan) 能画大鑑 (200 prints--27 of this last set are by Sōfū (1899-1963.) Sōfū wrote later that Kōgyo’s style was “vigorous, facile, and unrestrained.” Kōgyo’s publisher for both his nō prints and his nature studies was the printmaker Matsuki Heikichi, whose Daikokuya print shop in the Ryōgoku district of Tokyo was first established in 1763. Matsuki also published the graphic magazine Fūzoku gahō.3

1 Kindai no nōgaka: Tsukioka Kōgyoten (Chiba: Mizuta Museum of Art, 2005); Noh Theatre Prints: Kōgyo, 1869-1927 (Washington, D. C.: Shōgun Gallery, 1981); Nishino Haruo and Hata Akira, Nō Kyōgen jiten (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1999).

2 Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002) 318-9; Omote Akira and Amano Fumio, Iwanami Kōza Nō Kyōgen I: Nōgaku no rekishi (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1987) 158-166.

3 Kindai no nôgaka includes small reproductions of all 261 prints in Nôgakuzue and all 110 prints in Nôgaku hyakuban.

Richard J. Smethurst - UCIS Research Professor - Department of History - University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh Library System provides access to the digital images for personal, noncommercial, educational and research purposes only.

© 2011–

University Library System, University of Pittsburgh